Lukashenka’s war on Belarusians

Like every political surprise, the snowballing protest in Belarus now seems to have been inevitable. It wasn’t. Like every dictatorship before it, Lukashenka’s regime still appears invincible. It isn’t. Now of all times it is essential for Americans to understand the nuance and the context of what’s happening in Belarus. This could be America. This can still happen in America.

The reports from Belarus are blood-curdling. A photo of a five year old girl with a head injury, with a comment that a police vehicle rammed the car she was in. A video of riot police pinning a 15-year old boy to the ground and threatening him with a flash-bang grenade held to his face. Conflicting reports of a man dying from burns after the same kind of flash-bang exploded next to him: the government claims the man tried to throw it at the police, protesters say police shot at him (update: a video has turned up later that shows the victim bleeding and falling after getting shot in the chest at close range). A video of a man ran over by an armored mobile jail vehicle. Reports of tear gas grenades thrown into apartment windows.

People get grabbed on the streets, in the courtyards, yanked from their own apartments. A teenager reported being forced, along with other boys and girls his age, to stand on his knees in jail corridor for hours, while listening to cries of an adult being tortured in a room next door. Parents are spending days outside the jail waiting for a confirmation that their son or daughter is in that jail and not in a morgue, while listening to similar cries coming out of the windows.

Belarusians, scared into peacefulness by the generational trauma of losing 25% of country’s population in World War II, have not seen violence on this scale since 1944. The Belarusian temperament used to be described as “do whatever, just don’t start a war.” And now the country’s government is at war with its entire population. How did this happen?

Lukashenka has stolen many elections before: not a single election in Belarus since the one that’s made him president in 1994 has been internationally recognized as free and fair. The difference this year was plausibility.

Until this year, Lukashenka consistently polled in double digits, and the common sentiment was that even if the 83% of votes reported by his loyal Central Election Commission were a stretch, in theory he could get a majority or at least a plurality of votes.

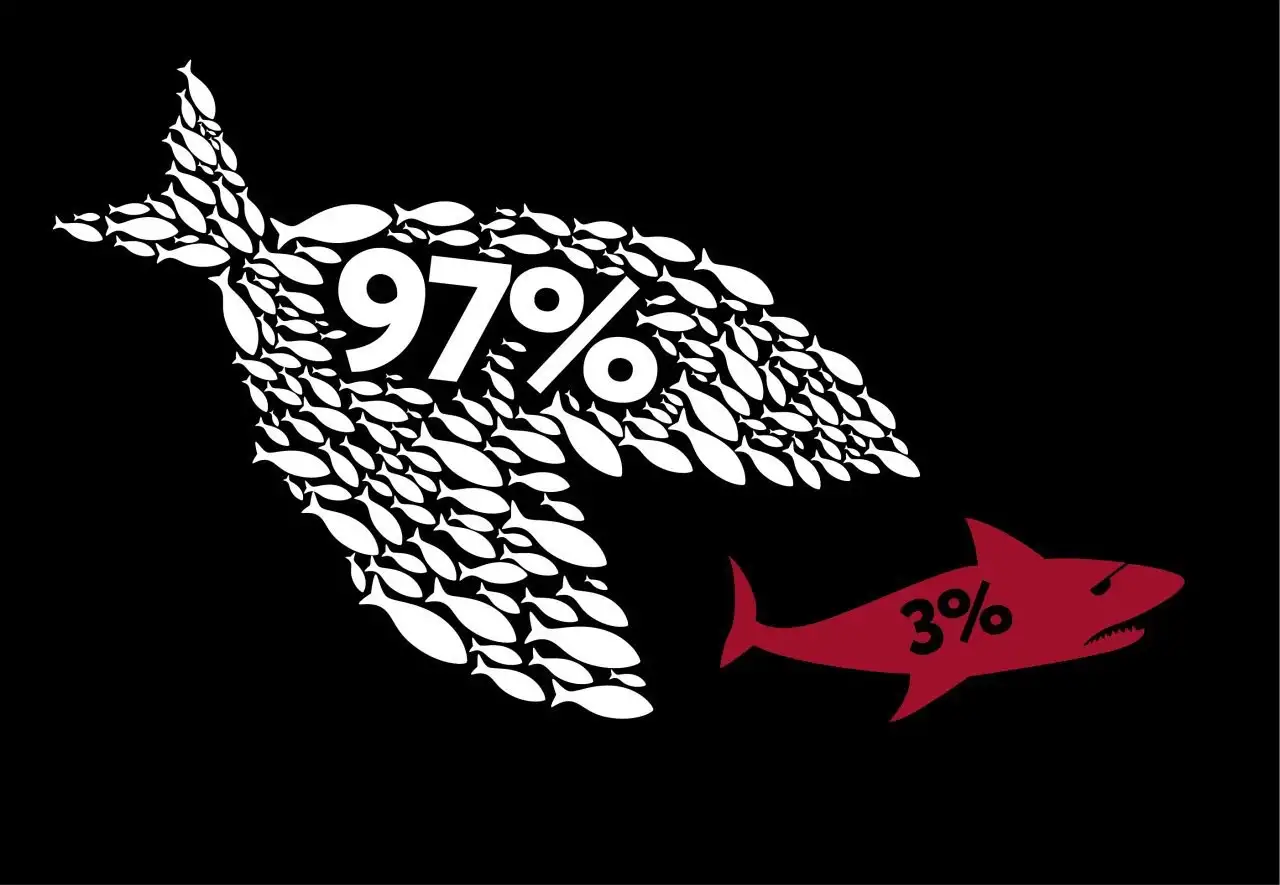

In May 2020, three out of five online polls ran by major Belarusian websites rated Lukashenka’s approval around 3%. This was a disaster. He immediately outlawed online political polls, and in July ran two state-sponsored polls that rated him around 70%. But the damage was done: people started calling him “Sasha 3%” (Sasha is diminutive for Alexander).

The most immediate cause of this dramatic drop in popularity was, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic. The price of living in a country without freedom of press, with no respect for human rights, with a government without any kind of accountability suddenly stopped being theoretical. Belarusians were used to being lied to by their government, but this time lies killed.

The government reported daily infection counts that remained just below 1,000 per day before going down without the government doing anything at all to stop the spread. The turnaround was so out of place that it attracted attention of the scientific community. A study of national SARS-CoV-2 daily infection counts (arXiv:2007.11779) found statistical anomalies in the data from Belarus and several other countries that could indicate tampering.

For ordinary Belarusians, it wasn’t a matter of statistics. Their friends and relatives were dying, small town cemeteries were filling up with fresh graves, and all they got was nonsensical diagnoses and insults from the president who blamed people dying of coronavirus complications for not taking good enough care of their own health.

People’s faith in an oppressive but competent leader who held their best interests at heart had already cracked after an ill-conceived and ultimately failed attempt to tax people for not having a job in 2017. Mishandling of both the pandemic itself and the public relations fallout from it has shattered it for good.

Confronting the reality of this novel situation made Lukashenka panic and pile on more mistakes. First, he has taken out all his top-polling opponents.

Mikola Statkevich — the indomitable veteran of Belarusian opposition with a record of dissent going back to 1990 and with a history of being forced to spend Belarusian presidential elections in jail — was denied registration as a candidate and was arrested on May 31.

Viktar Babaryka — a banker and philanthropist who polled around 50% in the same online polls that gave Lukashenka 3% — was also denied registration and was arrested on June 11.

Valery Tsepkalo — former Belarusian ambassador to US and Mexico and the founder of the Belarus Hi-Tech Park — wasn’t arrested, but most of the signatures collected by his campaign were rejected by CEC.

Siarhei Tsikhanouski — a video blogger with a massive following on YouTube — was arrested for the first time as soon as he announced his intent to run, and was kept in jail until May 20, long enough to make him miss the registration deadline. His wife Sviatlana applied for registration in his stead, and that’s where Lukashenka has made his next mistake.

Being a social conservative, Lukashenka underestimated women. Being incapable of empathy himself, he underestimated people’s capacity for compassion. He assumed that, unlike her husband, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya is not a threat. So he arrested Siarhei again and allowed Sviatlana to join his lineup of safe spoiler candidates.

It was bad enough that eliminating all high-polling men from the race and leaving someone he considered weak has indirectly confirmed that his 3% online polls rating is accurate enough to have him worried. But his bigger mistake was underestimating women.

Three weeks before the election, three women left in charge of three campaigns started by three men got together and agreed to join forces. The photo of Maria Kolesnikova with her hands in shape of a heart, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya raising up a fist, and Veronika Tsepkalo holding up a victory sign has instantly become iconic, and the corresponding words “Love. Might. Win.” became the rallying cry of their new United Headquarters.

Supported by the best logistics and creative minds of all three campaigns, the trio has set off on a blitz tour across Belarus and gathered unexpectedly large crowds even in small towns. In all previous elections, opposition candidates received significantly stronger support in the more liberal and more nationally self-aware capital, the rest of the country remained apprehensive of democracy and even more so of nationalism.

The campaign of three women seeking no power other than to bust the men — and the rest of the country — out of jail broke through all that and has drawn in people of all ages and political persuasions. It turned out that Belarusians who had reservations about helping men come to power did not at all mind helping women fight back against power.

United campaign’s first rally in Minsk gathered over 7,000 people. Their second rally in Minsk gathered 65,000. After the indivisible three graces gathered 7,400 in Baranovichi and 18,000 in Brest, the government decided not to find out how many people are going to come to their third rally in Minsk and hijacked all six Minsk locations reserved by the campaign with unrelated activities, most notably a holiday in honor of the Railway Troops — a military regiment that hasn’t existed for over a decade.

While the city was able to disrupt the rally, they couldn’t stop it from becoming another media win. The campaign redirected their supporters from the initially planned Bangalore Square to the nearby Kievsky Square. When the sound engineers running the city-sponsored concert in Kievsky Square learned that the concert was just a cover for disrupting the rally, they replaced their scheduled programming with a Perestroika hit “We Expect Change.” The opposition’s meme collection was enriched by a poster of the two young men raising hands making victory signs and a Forrest Gump worthy video of a city official trying to yank cables out of loudspeakers.

What happened next is a study in how high voter turnout makes falsifications harder and why it’s important to vote even when you expect your vote to be stolen.

Vote falsifications in Belarus traditionally — yes, 26 years is long enough for observations to turn into traditions — leaned on two principal methods: outright fabrication of early votes and misclassification of ballots by polling station counters. Belarusian elections still only use hand-marked paper ballots, this complicates tabulation falsifications.

Early votes are the easiest to steal because they are counted behind closed doors. The problem with this method is that some of the people the early votes got attributed to will show up in person and see somebody else’s signature next to their name in the ballot issue log. This is exactly what happened to my mother-in-law. When she reported this to observers, they asked her to line up behind four other people waiting to submit a formal complaint because their votes were also stolen in the early vote.

This time, the unprecedented gap between real and target vote percentages forced the CEC to get greedy and report that up to 40% of the people voted early. In polling station with higher than 60% voter turnout this presented an obvious problem: total turnout over 100%. Polling station commissions had to scramble to discard enough early votes to make room.

To make it harder for independent observers to detect misattribution of ballots, this year CEC completely banned observers from polling stations. This is how the famous photo of a man standing on a stool peering into a window with binoculars came to be: an observer trying his best to watch the count.

Belarus justified its reputation of the hi-tech capital of Eastern Europe by coming up with a novel counter to this falsification method: a team of programmers went on a hackathon and in just a few days built the Golos app where any Belarusian could register and submit a photo of their filled in ballot along with a reference to the polling station where they cast their vote.

By August 9, 1.2 million people, roughly 20% of all eligible voters in Belarus, registered in Golos. While the primary goal of the app was to detect fraud at polling stations level, this number is high enough to challenge even the national results published by CEC, where Tsikhanouskaya’s 10% of votes and 84% total turnout add up to approximately 0.5 million votes.

When the state-run Beltelecom, the company that controls all Internet access in Belarus, blocked access to Golos, Belarusians backed this up with a low-tech fix and recommended that Tsikhanouskaya supporters fold their ballots into an accordion to make it easier for observers peeking through windows to see when their ballots get put in a wrong stack.

These challenges forced the government to fall back to messing with tabulations. At a polling station in Vitebsk, the head of the city district was recorded demanding that the commissioners, mostly teachers from local schools, swap the counts for two candidates:

“I have a very harsh proposal for you: rewrite the minutes and radically change the numbers between the third and the fourth candidates. I can agree that Tsikhanouskaya got enough votes. But we have different tasks and different problems that we need to solve. Today, and later, on the first day of school, and on Teacher’s Day, and so on, you’ll need to be prepared. Do you get my meaning? So let us solve this. So that you don’t stick out in the district, so that we don’t have two apartment blocks on Frunze St. at one position and the rest at another, so that we don’t have street fights tomorrow, let’s solve this in unison.”

The head of the polling station commission later confirmed authenticity of the recording.

At some polling stations, the commissions refused to change the numbers and posted the results showing a landslide win by Tsikhanouskaya.

For older people who opposed Lukashenka throughout the 26 years of his rule, this blatant and thoroughly documented falsification of election results wasn’t a surprise. For people who used to support Lukashenka and vote for him and who used to disbelieve the complains about preceding elections, it was a shock.

When they peacefully marched in protest, completely unprepared for violence — wearing shorts, light dresses, and flip-flops, armed with nothing but white wristbands — they were in for another shock. They found out the hard way that the police wasn’t there to protect them, the police came to protect the unelected president from them.

The consistent non-violence of the protests in Belarus even in the face of unrestrained police brutality proves false a lie that worked in Lukashenka’s favor in 2015 and that he has tried to recycle in 2020.

In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he leaned heavily on the national independence card and presented himself as someone who protected Belarus from getting integrated into Russia. Lukashenka’s opponents were so worried that Russia, emboldened by its success in Ukraine, would use violent protests as pretext for invading and annexing Belarus, that they didn’t even try to fight back, and allowed 2015 to become the most quiet of Lukashenka’s elections to date.

To bolster this myth in 2020, Lukashenka detained a group of mercenaries and claimed that Russia sent them to Belarus to start violent protests and annex the country. It almost worked: Belarusian conversations on social networks turn to wondering whether Tsikhanouskaya is a Manchurian candidate planted by Russia. The united campaign countered by starting to speak Belarusian instead of Russian at their rallies and declaring that Belarus doesn’t need integration with Russia.

Subsequent actions of both Lukashenka and Putin demonstrated that the mercenaries story was never real. Lukashenka ignored requests from Ukraine to hand over the mercenaries who were listed in the database of Donbas militants, and instead promised to send them back to Russia. In turn, Putin was among the first to congratulate Lukashenka after the election.

While the historic context of the relationship between Belarus and Russia is complicated and goes back centuries, the relationship between Lukashenka and Russia’s leadership has been a straightforward “oil for kisses” since the very first years of his rule.

Lukashenka’s presidency would not have survived the 1996 constitutional crisis without Russia’s help. Belarusian parliament (at the time called the Supreme Council) was ready to impeach Lukashenka over his attempt to rewrite the country’s constitution by referendum. A delegation of top Russian officials took a red-eye flight to Minsk to protect the newly launched Commonwealth of Belarus and Russia and leaned on parliament leaders to cancel the vote.

Then speaker Syamyon Sharetski now lives in United States as a political refugee. I met him a few years ago at a meetup of Belarusians in San Francisco Bay Area. I remember him recounting how the Russians warned that impeaching Lukashenka could start a civil war and persuaded him that allowing Lukashenka to serve the remainder of his term would be the lesser evil.

The remainder of Lukashenka’s term went on an on, and so did the pattern of exchanging bits and pieces of Belarusian independence for subsidies that enabled him to “pay the pensions on time”.

In 1999, a Union State between Russia and Belarus was established.

In 2007, Gazprom was allowed to acquire controlling interest in the Belarusian gas pipeline operator Beltransgaz.

In 2010, a customs union between the countries protected the Russian car manufacturers from having to compete against used cars imported by Belarusians from Europe.

In 2017, Zapad-2017 joint military exercise that imitated a full-scale war along the border with Lithuania has integrated Belarusian army into Russian command structures.

In 2018 — just as Russia started looking to Bitcoin as a way to protect its money from US sanctions — Belarus legalized cryptocurrencies.

Lukashenka is not going to cede power voluntarily, and Putin is not going to back away from supporting him. Putin has invaded Ukraine to prevent that “fraternal nation” from becoming an encouraging example to his own people. A change in Belarusian leadership through peaceful protest and fair democratic elections would be a greater threat to his power than the Russian TV’s favorite scare of NATO expansion.

There is still room for peaceful transfer of power in Belarus. Lukashenka can’t maintain the illusion of legitimacy without support from the entire state bureaucracy, and some people who used to contribute to that support — from the polling station chiefs reporting and resisting fraud, to TV anchors resigning in horror of what’s been going on in the streets of Minsk, to retired paratroopers posting videos of throwing away their uniforms in disgust over actions of Belarusian riot police — are discovering new sources of courage and dignity within themselves. The rest still need a nudge.

The best way for the democracies of the world to provide that nudge is through targeted sanctions based on Magnitsky Act. Despite growing increasingly dependent on Russia, Belarus is more integrated into the global community than ever before. Many of the mid-level decision makers in Belarus — both in the government and in the private sector — would rather change jobs than get included in a list that would turn them and their businesses into toxic assets.

Confronted with tear gas, rubber bullets, flash-bangs, beatings, arrests, torture, and long prison terms, Belarusians continue to march peacefully. They count on support from United States and European Union. Will that support come?

(Karolina Pansevič, DELFI)